Separate, never equal:

White Schools, Colored Schools

Plessy v. Ferguson, an 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision, declared “separate but equal” constitutional. Armed with Plessy, white Southerners enshrined Jim Crow customs and laws: segregated trains, buses, fairs, restaurants, motels and hotels, parks, beaches, swimming pools — and schools. South Carolina’s 1895 constitution required “Separate schools shall be provided for children of the white and colored races, and no child of either race shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided for children of the other race.”

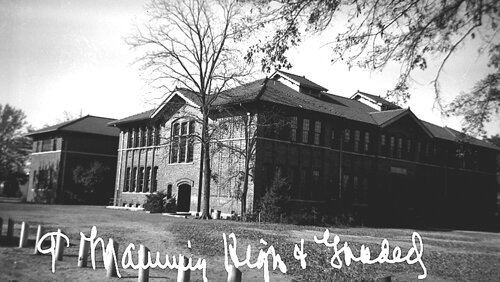

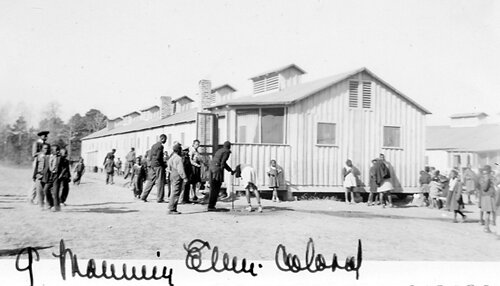

Blatantly unequal conditions for South Carolina’s black school children existed despite black parents’ efforts to provide buildings themselves and to collect school fees. In the 1930s, NAACP legal counsel Charles Hamilton Houston toured South Carolina with a movie camera and filmed the shocking contrasts: white children entering two-story brick schools and playing basketball on paved courts, black children entering decrepit former hunting lodges and sweeping dirt yards. You can watch Hamilton’s “A Study of Educational Inequalities in South Carolina,” reel 1, as well as outtakes on reel 2, at archive.org.

Houston’s film, presented by the NAACP in 1936, documented the woeful conditions for black children, who often attended school in decaying donated buildings since local Districts and the State provided very little. at the time of the film, South Carolina spent a total of $10.1 million on white schools and $1.3 million on black schools. Houston filmed a one-room school with 68 students, no desks, no tables, no stove, and a privy across railroad tracks (left). He filmed a Building donated by Mount Ararat Baptist Church in York County for school use— until it became uninhabitable (middle). the district furnished black children no buildings or supplies And only one teacher’s salarY. He filmed a school two miles from Columbia, South Carolina’s Capital, condemned by white authorities but not replaced, leaving 800 parents and children, such as these (right), without a local school. RUral families needed nearby schools; the state provided School bus Transportation only for white children.

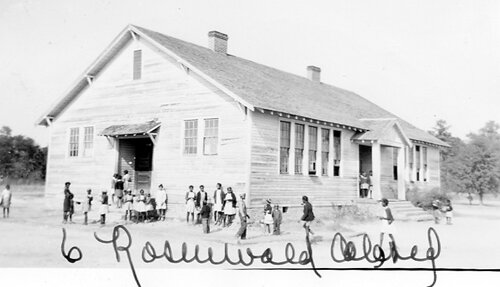

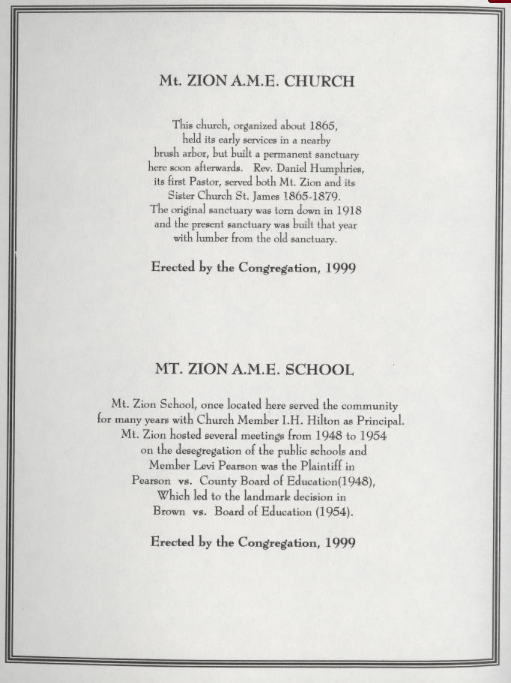

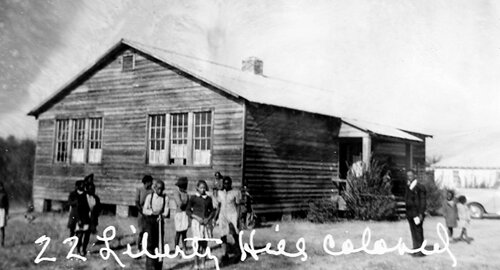

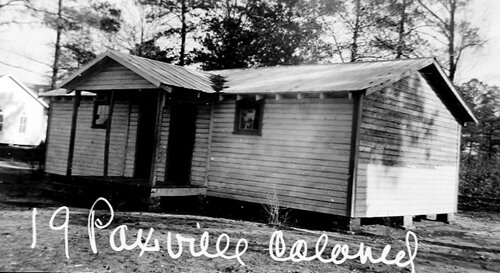

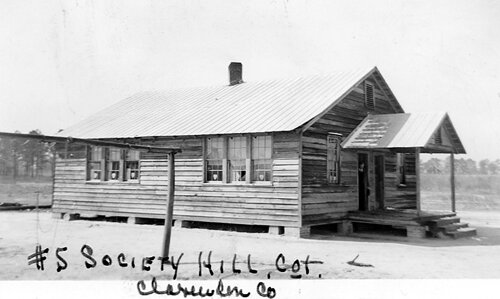

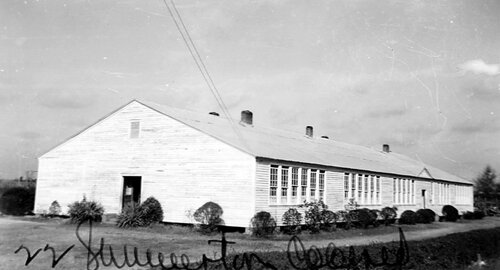

Booker T. Washington, President of the Tuskegee Institute, and Julius RosenWald, president of SearS, Roebuck and Co., stepped in, Aware of white southerners’ resistance or indifference to educating black children. between 1917 and 1932, Washington and Julius Rosenwald Aided in the construction of 5,000 rural schools for black children, 481 in South Carolina. The Rosenwald Fund required the participation of Black parents in the funding and building of the schools as well as the acceptance of white school Boards. at least three schools — from left, Rosenwald, Felton Rosenwald, and Mt. Zion AME schools — housed students in Clarendon County. PHOTOS COURTESY OF South Caroliniana Library, USC; the SC DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY’S INSURANCE FILE PHOTOGRAPHS, 1935-1950; and the SCDAH Rosenwald Schools Database, which Also Includes Manning and St. Mark schools.

In 1940, 2,296 white students and 6,081 black students attended Clarendon County schools. The far fewer white students attended schools that were valued at $390,600 compared to a $64,285 valuation for black students’ schools. The district spent $103,936 on white students’ education compared to $47,939 for black students’ education. Female teachers in white elementary schools were paid $782 a school year compared to $309 for female teachers in black elementary schools despite black teachers serving far more students.

In 1950, little had changed. South Carolina spent on instruction $91.77 per white pupil compared to $58.82 per black pupil. White men ran the legislature and all county school boards. While black people composed 70 percent of Clarendon County’s population, white people owned 85 percent of the land and believed that paying the majority of the taxes meant they rightfully received almost all the benefits.